Ultimo aggiornamento 2021-12-27 16:24:34

INTRODUZIONE . Considerando la crescente domanda di riproduzione assistita tecnologie (ART) e contemporaneamente la sempre maggiore età delle donne che desiderano una gravidanza, la valutazione della riserva funzionale ovarica è resa quasi necessaria non solo per uno studio preliminare delle pazienti ma soprattutto per valutare l’outcome gravidico da parte di medici e delle stesse coppie interessate ed elaborare protocolli di stimolazione personalizzati e più efficaci (1-10). I marker più comunente utilizzati e più affidabili sono quattro: l’età della paziente, l‘ormone antimulleriano (AMH), il volume ovarico e la conta dei follicoli antrali precoci (AFC).

Nessuno di essi si è dimostrato in grado di sondare la qualità del pool dei follicoli primordiali e quindi, il potenziale riproduttivo a lungo termine [3-7].

L’età è considerata il più importante fattore determinante per la qualità e la quantità della riserva follicolare. I follicoli diminuiscono significativamente con l’avanzare dell’età di una donna (v. grafico). Inoltre la fecondabilità degli ovociti diminuisce significativamente dopo i 30 anni [8]. La prevalenza dell’infertilità aumenta significativamente dopo i 35 anni e il 99% delle pazienti >45 anni à sterile [9]. Il declino della fertilità può essere attribuito, oltre alla diminuzione del numero degli ovociti, a fattori genetici, fumo, alcool, droghe e numerosi eventi associati con l’avanzare dell’età, compresi la qualità dell’ovocita, la frequenza e l’efficienza dell’ovulazione, le patologie uterine e annessiali, malattie metaboliche come le cardiopatie, obesità, diabete mellito e ipertensione arteriosa [10]. Donne di età >38 anni, sottoposte a inseminazione artificiale con sperma di donatore o sottoposte a cicli PMA presentano un pregnancy rate inferiore al 50% rispetto a donne <25 anni [13-16].

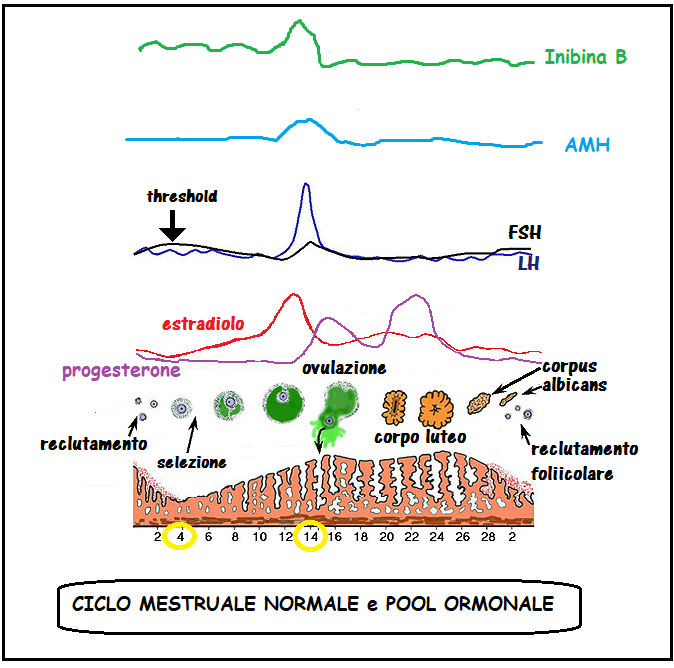

Durata del ciclo mestruale –I cicli mestruali hanno una durata di 23-32 giorni con una media di 28 giorni ed è condizionata dalla lunghezza della fase follicolare [17]. Un graduale accorciamento del ciclo può iniziare dopo i 38 anni circa in parallelo con livelli sierici più elevati di ormone follicolare stimolante (FSH) e livelli sierici più bassi di ß-inibina [18]. L’accorciamento della durata del ciclo dipendente dall’età è correlato con fasi follicolari accorciate; ci sono prove che il meccanismo alla base di ciò è da imputare allo scarso numero di follicoli antrali residui e conseguente diminuita produzione di ß-inibina che a sua volta induce un aumento della secrezione di FSH [19-21]. Le percentuali di gravidanza sono significativamente ridotte tra le donne con cicli di durata inferiore a 28 giorni e, se l’interferenza dell’età è escluso, i tassi di gravidanza sono quasi il doppio tra donne con cicli ≥28 giorni rispetto a quelle con cicli <26 giorni [21].

Test ormonali statici – La determinazione dei valori sierici dell’FSH al 2-3° giorno del ciclo è il test endocrino più studiato e utilizzato nella determinazione della riserva ovarica [6,22]. Storicamente, la combinazione di FSH basale (2-3° giorno del ciclo) ed età è risultata essere più affidabile rispetto alla sola età nel predire l’esito della fecondazione in vitro. Molti centri di fecondazione in vitro, quindi, continuano a fare affidamento sulle misurazioni basali dell’FSH sierico, nonostante le limitazioni derivate dalla sua grande variabilità all’interno dello stesso ciclo e tra i diversi cicli mestruali e interferenze di fattori esterni come il fumo [23,24]. In donne di età <40 anni si osserva una ridotta fertilità quando i livelli sierici di FSH al 3° giorno del ciclo superano 8 IU/L, mentre non è stato possibile determinare alcuna associazione per i livelli inferiori [25]. I marker associati di FSH basale e la conta di follicoli antrali iniziali (2-7 mm) (AFC) sono da considerare fattori predittivi significativi di outcome gravidico spontaneo [26]. In donne con livelli di FSH ≥15 UI/mL, sottoposte a cicli PMA, si recluta un minor numero di follicoli in assoluto e un numero di cicli annullati maggiore di donne con livelli inferiori di FSH, senza differenze significative nelle dosi di gonadotropina somministrate [27-29]. Inoltre, è stato di recente dimostrato che i tassi di gravidanza nelle donne di età <35 anni con FSH basale elevato erano superiori a quelli di donne anziane con livelli normali dell’ormone [30,31], rafforzando il concetto che l’età è da considerare come principale marker di riserva ovarica.

L’FSH continua ad essere un test interessante per l’indagine sulla riserva ovarica perché è un esame semplice e di basso costo nelle pazienti infertili [31], endometriosiche [32] o nelle pazienti di età superiore ai 35 anni [33]. Riserva ovarica diminuita è stata riscontrata in caso di FSH >14,9 mIU/mL al 3° giorno oppure se i livelli di FSH al 10° giorno erano superiori ai livelli osservati al 3° giorno [81]. Detto questo, il dato di alti livelli di FSH non dovrebbe essere utilizzato come criterio base per escludere le donne dal procedere con ART.

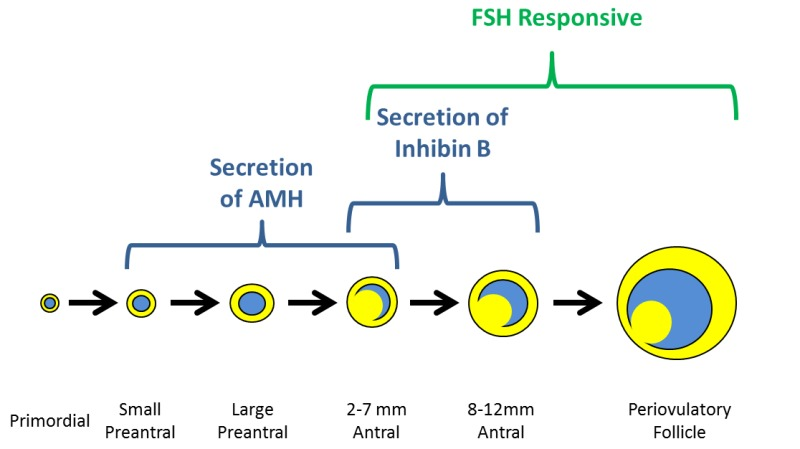

ß-inibina. Le inibine sono ormoni glicoproteici della superfamiglia dei fattori di crescita trasformanti β (TGF-β) secreti dalle cellule della granulosa e della teca [34]. I valori sierici della ß-inibina nelle donne in età fertile sono: fase follicolare precoce: 50-60 pg/ml; fase pre-ovulatoria: 133-150 pg/mL; fase luteale: ≅20 pg/mL

La ß-inibina inibisce la secrezione ipofisaria di FSH [35] e svolge un’azione paracrina sui follicoli in via di sviluppo, stimolata dall’associazione dell’FSH stesso con il fattore di crescita insulino-simile I [36, 37]. La β-inibina è il marker principale della crescita follicolare, infatti essa è in stretta correlazione con il diametro follicolare e la secrezione del 17-β-estradiolo (38). Sulle pazienti infertili di età compresa tra 24 e 40 anni si sono dimostrate significative correlazioni negative tra ß-inibina basale e FSH basale, e significativa correlazione positiva tra ß-inibina basale e conta dei follicoli antrali precoci (AFC) [38-42].

Pazienti con ß-inibina sierica ridotta presentano scarso outcome gravidico in cicli PMA e scarso numero di follicoli antrali anche se hanno un FSH normale al 3° giorno del ciclo [43]. Inoltre c’è una correlazione significativa tra il numero di ovociti recuperati e concentrazione sierica di ß-inibina e tutte le pazienti con livello sierico di inibina-B >100 pg/mL producono >6 ovociti [44,45]. Altri studi, tuttavia, sconsigliano l’uso di ß-inibina da sola come predittore affidabile della riserva ovarica [46.47]. La revisione sistematica di Broekmans et al. [6] consiglia con insistenza i medici ad essere consapevoli dell’alto tasso di falsi positivi nella determinazione dell’inibina-B basale.

Estradiolo (E2). I livelli basali di E2 possono fornire ulteriori informazioni utili per la valutazione della riserva ovarica. Gli aumenti di E2 sierico sono intesi come conseguenza dello sviluppo follicolare [18]. Misurazione sia di FSH che di E2 al 3° giorno del ciclo basale può aiutare a diminuire l’incidenza dei test falsi negativi basati sulla misurazione del solo FSH; quando entrambi i marker sono precocemente elevati, è probabile che si verifichi una scarsa risposta ovarica [18]. Considerando la bassa accuratezza predittiva e la mancanza di alta sensibilità e livelli di cutoff di specificità, la sua importanza come marker di valutazione per riserva ovarica è trascurabile [6].

Ormone antimulleriano (AMH) – indicato anche come sostanza inibitrice di Muller, è un ormone glicoproteico della superfamiglia TGF-β espresso dalle cellule della granulosa non appena i follicoli primordiali sono reclutato [50]; la sua espressione viene mantenuta fino a che i follicoli raggiungono un diametro di circa 6 mm, quando i follicoli pre-antrali sono selezionati per la dominanza [51] e la crescita follicolare è controllato dall’azione dell’FSH [52]. L’attività biologica dell’AMH nelle donne non è completamente compresa, ma i dati degli ultimi anni suggeriscono che può agire come modulatore del reclutamento follicolare e come regolatore della steroidogenesi ovarica [50, 53]. AMH è noto avere un effetto inibitorio sul pool di follicoli primordiali, agendo sulle cellule della pregranulosa per limitarne il numero di unità follicolari reclutabili e, successivamente, come fattore determinante nel permettere la crescita FSH-dipendente dei follicoli ovarici [52-56]. Dalle precedenti disposizioni, la determinazione di AMH ha stato proposto nella pratica clinica per la previsione di riserva ovarica. AMH è considerato un marker affidabile per stimare la quantità e l’attività dei follicoli recuperabili nelle prime fasi di maturazione [43, 50, 52, 57-60]. Con questi valori l’AMH presenta una soglia dell’80% di sensibilità e 93% di specificità. Una correlazione positiva è stata riscontrata tra i livelli sierici di AMH basali e il numero di ovociti prelevati e la percentuale di ovociti maturi [72-77]. Una significativa correlazione è stata invece evidenziata fra livelli sierici di AMH >2,7 ng/mL e tassi più elevati di impianto e gravidanza.

In conclusione una scarsa risposta alla stimolazione ovarica può essere associata a livelli sierici di AMH <1 ng/mL, risposta normale con livelli di 1-4 ng/mL e risposta elevata con livelli >4 ng/mL [60, 69,72, 79, 80].

I livelli sierici di AMH decrescono con l’età [61-63]. Rispetto a FSH, inibina-B ed E2, AMH ha il vantaggio della ridotta variabilità delle sue concentrazioni sieriche durante il ciclo mestruale [5, 64, 65]. I valori sierici medi sono 1,4±1,1 ng/ml, 1,43±1,08 ng/ml e 1,35±1,02 ng/ml rispettivamente in fase follicolare, periovulatoria e luteale [64-71].

Test ormonali dinamici Clomifene Citrato Challenge test (CCCT): 100 mg di clomifene citrato viene somministrato a donne di età ≥35 anni dai giorni 5–9 del ciclo mestruale. Una scansione ecografica delle ovaie e i livelli sierici di FSH, LH ed E2 vengono determinati precedentemente al 2-3° giorno del ciclo e quindi nei giorni 10-11 del ciclo. Al 10° giorno l’FSH che in donne con riserva ovarica normale risulta più basso, mentre l’estradiolo risulta aumentato. Il test è considerato anomalo e quindi con prognosi sfavorevole alla fertilità se l’FSH è uguale o superiore al valore riscontrato al 3° giorno (83). Una recente metanalisi ha permesso di stabilire che il valore prognostico del CCCT è di poco superiore al dosaggio dell’FSH al 3° giorno per la diagnosi di “poor responders”.

Conteggio dei follicoli antrali (AFC). AFC ha dimostrato di essere un eccellente predittore di riserva ovarica con significativa superiorità in relazione ad altri marcatori fin quì analizzati [89–91]. Gli studi hanno anche dimostrato correlazioni significative tra AFC e gli altri test di riserva ovarica [92, 50,52]. La sola AFC dovrebbe consentire l’identificazione di “poor responders” con una sensibilità dell’l’89%, nonostante la bassa specificità [60]. A causa della bassa specificità l’AFC non deve essere utilizzato come criterio per l’esclusione dell’ART, ma come strumento di consulenza sulla bassa probabilità. AFC con una media di ≥10,1±3,0 follicoli antrali iniziali (2-7 mm) è riscontrata in pazienti normoresponders mentre AFC di <5,7±1,0 follicoli antrali classifica le pazienti “poor responders” [29,64,92,94].

Volume ovarico –

Durante l’età fertile, le ovaie subiscono variazioni morfovolumetriche correlate allo sviluppo ciclico ed atresia dei follicoli. Le normali dimensioni di un ovaio in età fertile sono 2,2-2,9 cm di lunghezza, 1,52,0 cm di larghezza e 1,5-3,0 cm di spessore (dimensione antero-posteriore) (11-14). Tradizionalmente il calcolo del volume ovarico è stato effettuato utilizzando la formula per l’elissoide (π/6 x diametro longitudinale x diametro anteroposteriore x diametro trasversale). La formula semplificata attualmente in uso è: 0,5 (che corrisponde alla approssimazione di π/6=0,5233) per lunghezza x larghezza x spessore. Il volume di un ovaio normale in età feconda è 10-15 cm3.

Le opinioni sulla valutazione del volume ovarico (VO) come un adeguato test di riserva gonadica non sono univoche. Molti AA. hanno riscontrato un numero ridotto di ovociti prodotti e ridotto pregnancy rate con volumi ovarici ridotti [94-96]. Infine, significative correlazioni erano state precedentemente trovate tra ridotto misure ovariche, età avanzata ed elevato FSH . sierico [97-103]. Quindi, OV da solo non dovrebbe essere considerato come un predittore di riserva ovarica, ma crediamo che, grazie alla sua semplicità e facilità d’uso, può essere incluso come esame di routine nelle procedure diagnostiche per la valutazione della riserva ovarica.

Flussimetria ovarica –

Con il color-power Doppler è possibile studiare la vascolarizzazione perifollicolare che appare più marcata attorno al follicolo dominante sì da configurare un frame noto come “ring of fire”. Alla scansione con Doppler pulsato le arteriole spirali perifollicolari mostrano un’alta impedenza e bassa velocità.

Gli indici di vascolarizzazione dell’ovaio dominante, del follicolo dominante e del corpo luteo, valutati con il 3D power Doppler, aumentano durante la fase follicolare restando alti anche dopo la rottura del follicolo e la formazione del corpo luteo. Ciò è dovuto alla formazione di nuovi vasi e all’aumento di fattori angiogenetici.

Il flusso sanguigno ovarico (OBF) è stato ampiamente valutato nella PMA [104] e correlazione negativa è stata riscontrata tra età e flusso sanguigno perifollicolare peri-ovulatorio. Un alto tasso di gravidanza si riscontra nelle donne con follicoli altamente vascolarizzati nella fase follicolare precoce. Nonostante quanto suddetto sia molto interessante, attualmente risultano ancora molti fattori discordanti che non permettono di utilizzare la flussimetria ovarica come fattore predittivo affidabile per la valutazione della riserva ovarica ⌈109-111].

References:

- H. Leridon, “30 years of contraception in France,” Contraception Fertilite Sexualite, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 435–438, 1998.

- F. I. Sharara and R. T. Scott Jr., “Assessment of ovarian reserve and treatment of low responders,” Infertility and Reproductive Medicine Clinics of North America, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 501–522,1997.

- A. Gougeon, “Regulation of ovarian follicular development in primates: facts and hypotheses,” Endocrine Reviews, vol.17, no. 2, pp. 121–155, 1996.

- K. P. Tremellen, M. Kolo, A. Gilmore, and D. N. Lekamge, “Anti-mullerian hormone as a marker of ovarian reserve,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 20–24, 2005.

- R. Fanchin, J. Taieb, D. H. M. Lozano, B. Ducot, R. Frydman, and J. Bouyer, “High reproducibility of serum anti-Mullerian ¨hormone measurements suggests a multi-staged follicular secretion and strengthens its role in the assessment of ovarian follicular status,” Human Reproduction, vol. 20, no. 4, pp.923–927, 2005.

- F. J. Broekmans, J. Kwee, D. J. Hendriks, B. W. Mol, and C. B. Lambalk, “A systematic review of tests predicting ovarian reserve and IVF outcome,” Human Reproduction Update, vol.12, no. 6, pp. 685–718, 2006.

- B. R. de Carvalho, A. C. J. D. S. Rosa e Silva, J. C. Rosa e Silva, R. M. dos Reis, R. A. Ferriani, and M. F. Silva de Sa, “Ovarian reserve evaluation: state of the art,” ´ Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 311–322, 2008.

- M. J. Faddy, R. G. Gosden, A. Gougeon, S. J. Richardson, and J. F. Nelson, “Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: implications for forecasting menopause,” Human Reproduction, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 1342–1346, 1992.

- J. Menken, J. Trussell, and U. Larsen, “Age and infertility,” Science, vol. 233, no. 4771, pp. 1389–1394, 1986.

- T. Rowe, “Fertility and a woman’s age,” The Journal of Reproductive Medicine, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 157–163, 2006.

- D. B. Dunson, B. Colombo, and D. D. Baird, “Changes with age in the level and duration of fertility in the menstrual cycle,” Human Reproduction, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1399–1403,2002.

- D. Schwartz and M. J. Mayaux, “Female fecundity as a function of age. Results of artificial insemination in 2193 nulliparous women with azoospermic husbands,” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 306, no. 7, pp. 404–406,

1982. - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Report: National Summary, 2009, http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/art/Apps/NationalSummaryReport .aspx.

- F. Zegers-Hochschild, J. E. Schwarze, and V. Galdames, Eds., Red Latinoamericana de Reproduccion Asistida ´ , Registro Latinoamericano de Reproduccion Asistida, 2008.

- A. Z. Steiner and R. J. Paulson, “Oocyte donation,” Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 44–54, 2006.

- B. R. de Carvalho, I. D. O. Cabral, H. M. Nakagava, A. A. Silva, and A. C. P. Barbosa, “Woman’s age and ovarian response in ICSI cycles,” Jornal Brasileiro de Reproducao Assistida, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 24–27, 2010.

- L. A. Cole, D. G. Ladner, and F. W. Byrn, “The normal variabilities of the menstrual cycle,” Fertility and Sterility, vol.91, no. 2, pp. 522–527, 2009.

- L. Speroff and M. A. Fritz, “Female infertility,” in Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility, L. Speroff and M.A. Fritz, Eds., pp. 1015–1022, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa, USA, 7th edition, 2005.

- P. van Zonneveld, G. J. Scheffer, F. J. M. Broekmans et al., “Do cycle disturbances explain the age-related decline of female fertility? Cycle characteristics of women aged over 40 years compared with a reference population of young women,” Human Reproduction, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 495–501, 2003.

- N. A. Klein, A. J. Harper, B. S. Houmard, P. M. Sluss, and M. R. Soules, “Is the short follicular phase in older women secondary to advanced or accelerated dominant follicle development?” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 87, no. 12, pp. 5746–5750, 2002.

- T. Brodin, T. Bergh, L. Berglund, N. Hadziosmanovic, and J. Holte, “Menstrual cycle length is an age-independent marker of female fertility: results from 6271 treatment cycles of in vitro fertilization,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 90, no. 5, pp.

1656–1661, 2008. - T. Silberstein, D. T. MacLaughlin, I. Shai et al., “Mullerian inhibiting substance levels at the time of HCG administration in IVF cycles predict both ovarian reserve and embryo morphology,” Human Reproduction, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 159–163, 2006.

- C. B. Lambalk and C. H. de Koning, “Interpretation of elevated FSH in the regular menstrual cycle,” Maturitas, vol.30, no. 2, pp. 215–220, 1998.

- M. Al-Azemi, S. R. Killick, S. Duffy et al., “Multi-marker assessment of ovarian reserve predicts oocyte yield after ovulation induction,” Human Reproduction, vol. 26, no. 2, pp.414–422, 2011.

- J. W. van der Steeg, P. Steures, M. J. C. Eijkemans et al., “Predictive value and clinical impact of basal folliclestimulating hormone in subfertile, ovulatory women,” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 92, no. 6, pp. 2163–2168, 2007.

- M. L. Haadsma, H. Groen, V. Fidler et al., “The predictive value of ovarian reserve tests for spontaneous pregnancy in subfertile ovulatory women,” Human Reproduction, vol. 23,no. 8, pp. 1800–1807, 2008.

- M. Ashrafi, T. Madani, A. Seirafi Tehranian, and F.Malekzadeh, “Follicle stimulating hormone as a predictor of ovarian response in women undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for IVF,” International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 91, no. 1, pp. 53–57, 2005.

- M. Creus, J. Penarrubia, F. F ˜ abregues et al., “Day 3 serum inhibin B and FSH and age as predictors of assisted reproduction treatment outcome,” Human Reproduction, vol.15, no. 11, pp. 2341–2346, 2000

- E. R. Klinkert, F. J. M. Broekmans, C. W. N. Looman, J. D.

F. Habbema, and E. R. Te Velde, “The antral follicle count

is a better marker than basal follicle-stimulating hormone

for the selection of older patients with acceptable pregnancy

prospects after in vitro fertilization,” Fertility and Sterility,

vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 811–814, 2005. - M. Luna, L. Grunfeld, T. Mukherjee, B. Sandler, and A. B.

Copperman, “Moderately elevated levels of basal folliclestimulating hormone in young patients predict low ovarian

response, but should not be used to disqualify patients from

attempting in vitro fertilization,” Fertility and Sterility, vol.

87, no. 4, pp. 782–787, 2007. - J. M. van Montfrans, A. Hoek, M. H. A. van Hooff, C. H.

de Koning, N. Tonch, and C. B. Lambalk, “Predictive value

of basal follicle-stimulating hormone concentrations in a

general subfertility population,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 74,

no. 1, pp. 97–103, 2000. - B. R. de Carvalho, A. C. J. D. S. Rosa-E-Silva, J. C. RosaE-Silva, R. M. D. Reis, R. A. Ferriani, and M. F. Silva

de Sa, “Increased basal FSH levels as predictors of low- ´

quality follicles in infertile women with endometriosis,”

International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 110,

no. 3, pp. 208–212, 2010. - A. H. Watt, A. T. R. Legedza, E. S. Ginsburg, R. L. Barbieri,

R. N. Clarke, and M. D. Hornstein, “The prognostic value of

age and follicle-stimulating hormone levels in women over

forty years of age undergoing in vitro fertilization,” Journal

of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 264–

268, 2000. - F. J. Hayes, J. E. Hall, P. A. Boepple, and W. F. Crowley, “Differential control of gonadotropin secretion in the

human: endocrine role of inhibin,” The Journal of Clinical

Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 83, no. 6, pp. 1835–1841,

1998. - N. A. Klein, P. J. Illingworth, N. P. Groome, A. S. McNeilly,

D. E. Battaglia, and M. R. Soules, “Decreased inhibin B

secretion is associated with the monotropic FSH rise in older,

ovulatory women: a study of serum and follicular fluid levels

of dimeric inhibin A and B in spontaneous menstrual cycles,”

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 81,

no. 7, pp. 2742–2745, 1996. - D. A. Magoffin and A. J. Jakimiuk, “Inhibin A, inhibin B and

activin A in the follicular fluid of regularly cycling women,”

Human Reproduction, vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 1714–1719, 1997. - C. K. Welt and A. L. Schneyer, “Differential regulation of inhibin B and inhibin A by follicle-stimulating hormone and local growth factors in human granulosa cells from small antral follicles,” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 330–336, 2001.

- Groome NP, Illingworth PJ, O’Brien M, et al. 1996 Measurement of dimeric inhibin B throughout the human menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 81:1401–1405

- Muttukrishna S, McGarrigle H, Wakim R, Khadum I, Ranieri DM, Serhal P. Antral follicle count, anti-mullerian hormone and inhibin B: predictors of ovarian response in assisted reproductive technology? Bjog 2005;112:1384-90nction“. Menopause, 2008 Jul-Aug; 15 (4 Pt 1): 603-12

- Seifer DB, Lambert-Messerlian G, Hogan JW, et al. Day 3 serum inhibin-B is predictive of assisted reproductive technologies outcome. Fertility and Sterility 1997;67:110-4

- Creus M, Penarrubia J, Fàbregues F, et al. Day 3 serum inhibin B and FSH and age as predictors of assisted reproduction treatment outcome. Hum Reprod 2000; 15: 2341-6

- Eldar-Geva T, Robertson DM, Cahir N, et al. Relationship between serum inhibin A and B and ovarian follicle development after a daily fixed dose administration of recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85:607-13

- H. Tinkanen, M. Blauer, P. Laippala, P. Tuohimaa, and E. Kujansuu, “Correlation between serum inhibin B and other indicators of the ovarian function,” European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, vol. 94, no.1, pp. 109–113, 2001.

- D. B. Seifer, G. Lambert-Messerlian, J. W. Hogan, A. C.Gardiner, A. S. Blazar, and C. A. Berk, “Day 3 serum inhibin-B is predictive of assisted reproductive technologies outcome,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 67, no. 1, pp. 110–114,1997.

- T. Eldar-Geva, E. J. Margalioth, A. Ben-Chetrit et al., “Serum inhibin B levels measured early during FSH administration for IVF may be of value in predicting the number of oocytes to be retrieved in normal and low responders,” Human Reproduction, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 2331–2337, 2002.

- J. Penarrubia, S. Peralta, F. F ˜ abregues, F. Carmona, R. Casamitjana, and J. Balasch, “Day-5 inhibin B serum concentrations and antral follicle count as predictors of ovarian response and live birth in assisted reproduction cycles stimulated with gonadotropin after pituitary suppression”. Fertility and Sterility, vol. 94, no. 7, pp. 2590–2595, 2010.

- S. L. Corson, J. Gutmann, F. R. Batzer, H. Wallace, N. Klein, and M. R. Soules, “Inhibin-B as a test of ovarian reserve for infertile women,” Human Reproduction, vol. 14, no. 11, pp.2818–2821, 1999.

- J. B. Scheffer, D. M. Lozano, R. Frydman, and R. Fanchin, “Relationship of serum anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin B, estradiol and FSH on day 3 with ovarian follicular status,” Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetricia, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 186–191, 2007.

- M. McIlveen, J. D. Skull, and W. L. Ledger, “Evaluation of the utility of multiple endocrine and ultrasound measures of ovarian reserve in the prediction of cycle cancellation in a high-risk IVF population,” Human Reproduction, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 778–785, 2007.

- J. L. Frattarelli, P. A. Bergh, M. R. Drews, F. I. Sharara, and R. T. Scott Jr., “Evaluation of basal estradiol levels in assisted reproductive technology cycles,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 518–524, 2000.

- F. L. Licciardi, H. C. Liu, and Z. Rosenwaks, “Day 3 estradiol serum concentrations as prognosticators of ovarian stimulation response and pregnancy outcome in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization,” Fertility and Sterility, vol.64, no. 5, pp. 991–994, 1995.

- D. B. Smotrich, M. J. Levy, E. A. Widra, J. L. Hall, P. R. Gindoff, and R. J. Stillman, “Prognostic value of day 3 estradiol on in vitro fertilization outcome,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 64, no. 6, pp. 1136–1140, 1995.

- B. R. de Carvalho, A. C. J. D. S. Rosa E Silva, J. C. Rosa E

Silva, R. M. Dos Reis, R. A. Ferriani, and M. F. Silva De Sa,´

“Use of ovarian reserve markers and variables of response to

gonadotropic stimulus as predictors of embryo implantation

in ICSI cycles,” Jornal Brasileiro de Reproducao Assistida, vol.

13, no. 3, pp. 26–29, 2009. - C. Fic¸icioglu, T. Kutlu, E. Baglam, and Z. Bakacak, “Early ˇ

follicular antimullerian hormone as an indicator of ovarian ¨

reserve,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 85, no. 3, pp. 592–596,

2006. - R. Fanchin, L. M. Schonauer, C. Righini, J. Guibourdenche, ¨

R. Frydman, and J. Taieb, “Serum anti-Mullerian hormone ¨

is more strongly related to ovarian follicular status than

serum inhibin B, estradiol, FSH and LH on day 3,” Human

Reproduction, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 323–327, 2003. - C. Weenen, J. S. E. Laven, A. R. M. von Bergh et al.,

“Anti-Mullerian hormone expression pattern in the human ¨

ovary: potential implications for initial and cyclic follicle

recruitment,” Molecular Human Reproduction, vol. 10, no. 2,

pp. 77–83, 2004. - J. A. Visser and A. P. N. Themmen, “Anti-Mullerian hormone ¨

and folliculogenesis,” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology,

vol. 234, no. 1-2, pp. 81–86, 2005. - A. L. L. Durlinger, P. Kramer, B. Karels et al., “Control of

primordial follicle recruitment by anti-mullerian hormone

in the mouse ovary,” Endocrinology, vol. 140, no. 12, pp.

5789–5796, 1999. - A. L. L. Durlinger, M. J. G. Gruijters, P. Kramer et al., “AntiMullerian hormone attenuates the e ¨ ffects of FSH on follicle development in the mouse ovary,” Endocrinology, vol. 142, no. 11, pp. 4891–4899, 2001

- N. di Clemente, B. Goxe, J. J. Remy et al., “Inhibitory effect of

AMH upon the expression of aromatase and LH receptors

by cultured granulosa cells of rat and porcine immature

ovaries,” Endocrine, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 553–558, 1994. - J. A. Visser, A. L. L. Durlinger, I. J. J. Peters et al., “Increased

oocyte degeneration and follicular atresia during the estrous

cycle in anti-Mullerian hormone null mice,” ¨ Endocrinology,

vol. 148, no. 5, pp. 2301–2308, 2007. - I. A. J. van Rooij, F. J. M. Broekmans, E. R. Te Velde et al.,

“Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels: a novel measure of ¨

ovarian reserve,” Human Reproduction, vol. 17, no. 12, pp.

3065–3071, 2002. - E. R. Te Velde and P. L. Pearson, “The variability of female

reproductive ageing,” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 8,

no. 2, pp. 141–154, 2002. - M. J. G. Gruijters, J. A. Visser, A. L. L. Durlinger, and A. P. N.

Themmen, “Anti-Mullerian hormone and its role in ovarian ¨

function,” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, vol. 211, no.

1-2, pp. 85–90, 2003. - S. Muttukrishna, H. McGarrigle, R. Wakim, I. Khadum,

D. M. Ranieri, and P. Serhal, “Antral follicle count, antimullerian hormone and inhibin B: predictors of ovarian

response in assisted reproductive technology?” An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 112, no. 10,

pp. 1384–1390, 2005. - A. de Vet, J. S. E. Laven, F. H. de Jong, A. P. N. Themmen,

and B. C. J. M. Fauser, “Antimullerian hormone serum levels: ¨

a putative marker for ovarian aging,” Fertility and Sterility,

vol. 77, no. 2, pp. 357–362, 2002. - S. M. Nelson, M. C. Messow, A. M. Wallace, R. Fleming,

and A. McConnachie, “Nomogram for the decline in serum

antimullerian hormone: a population study of 9,601 infertil- ¨

ity patients,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 95, no. 2, pp. 736–741,

2010. - J. Van Disseldorp, M. J. Faddy, A. P. N. Themmen et al., “Relationship of serum antimullerian hormone concentration to ¨

age at menopause,” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and

Metabolism, vol. 93, no. 6, pp. 2129–2134, 2008. - E. A. Elgindy, D. O. El-Haieg, and A. El-Sebaey, “AntiMullerian hormone: correlation of early follicular, ovulatory ¨

and midluteal levels with ovarian response and cycle outcome

in intracytoplasmic sperm injection patients,” Fertility and

Sterility, vol. 89, no. 6, pp. 1670–1676, 2008. - A. La Marca, G. Stabile, A. Carducci Artenisio, and A. Volpe,

“Serum anti-Mullerian hormone throughout the human

menstrual cycle,” Human Reproduction, vol. 21, no. 12, pp.

3103–3107, 2006. - S. Tsepelidis, F. Devreker, I. Demeestere, A. Flahaut, C.

Gervy, and Y. Englert, “Stable serum levels of anti-Mullerian ¨

hormone during the menstrual cycle: a prospective study in

normo-ovulatory women,” Human Reproduction, vol. 22, no.

7, pp. 1837–1840, 2007. - S. L. Broer, B. W. J. Mol, D. Hendriks, and F. J. M. Broekmans,

“The role of antimullerian hormone in prediction of outcome after IVF: comparison with the antral follicle count,”

Fertility and Sterility, vol. 91, no. 3, pp. 705–714, 2009. - T. H. Lee, C. H. Liu, C. C. Huang, K. C. Hsieh, P. M. Lin,

and M. S. Lee, “Impact of female age and male infertility

on ovarian reserve markers to predict outcome of assisted

reproduction technology cycles,” Reproductive Biology and

Endocrinology, vol. 7, article 100, 2009. - L. G. Nardo, T. A. Gelbaya, H. Wilkinson et al., “Circulating

basal anti-Mullerian hormone levels as predictor of ovarian ¨

response in women undergoing ovarian stimulation for in

vitro fertilization,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 92, no. 5, pp.

1586–1593, 2009. - S. Muttukrishna, H. Suharjono, H. McGarrigle, and M.

Sathanandan, “Inhibin B and anti-Mullerian hormone:

markers of ovarian response in IVF/ICSI patients?” An

International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 111,

no. 11, pp. 1248–1253, 2004. - R. Fadini, R. Comi, M. Mignini Renzini et al., “Antimullerian hormone as a predictive marker for the selection

of women for oocyte in vitro maturation treatment,” Journal

of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 501–

508, 2011. - A. La Marca, S. Giulini, A. Tirelli et al., “Anti-Mullerian ¨

hormone measurement on any day of the menstrual cycle

strongly predicts ovarian response in assisted reproductive

technology,” Human Reproduction, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 766–

771, 2007. - C. Gnoth, A. N. Schuring, K. Friol, J. Tigges, P. Mallmann,

and E. Godehardt, “Relevance of anti-Mullerian hormone

measurement in a routine IVF program,” Human Reproduction, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 1359–1365, 2008. - T. Irez, P. Ocal, O. Guralp, M. Cetin, B. Aydogan, and S.

Sahmay, “Different serum anti-Mullerian hormone concen- ¨

trations are associated with oocyte quality, embryo development parameters and IVF-ICSI outcomes,” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 284, no. 5, pp. 1295–1301, 2011. - D. B. Seifer, V. L. Baker, and B. Leader, “Age-specific serum

anti-Mullerian hormone values for 17,120 women presenting ¨

to fertility centers within the United States,” Fertility and

Sterility, vol. 95, no. 2, pp. 747–750, 2010. - K. Majumder, T. A. Gelbaya, I. Laing, and L. G. Nardo,

“The use of anti-Mullerian hormone and antral follicle count ¨

to predict the potential of oocytes and embryos,” European

Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology,

vol. 150, no. 2, pp. 166–170, 2010. - C. Takahashi, A. Fujito, M. Kazuka, R. Sugiyama, H. Ito, and

K. Isaka, “Anti-Mullerian hormone substance from follicular ¨

fluid is positively associated with success in oocyte fertilization during in vitro fertilization,” Fertility and Sterility, vol.

89, no. 3, pp. 586–591, 2008. - S. Arabzadeh, G. Hossein, B. H. Rashidi, M. A. Hosseini,

and H. Zeraati, “Comparing serum basal and follicular

fluid levels of anti-Mullerian hormone as a predictor of in ¨

vitro fertilization outcomes in patients with and without

polycystic ovary syndrome,” Annals of Saudi Medicine, vol.

30, no. 6, pp. 442–509, 2010. - A. La Marca, G. Sighinolfi, D. Radi et al., “Anti-Mullerian ¨

hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technology (ART),” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 16,

no. 2, Article ID dmp036, pp. 113–130, 2009. - S. M. Nelson, R. W. Yates, H. Lyall et al., “Anti-Mullerian ¨

hormone-based approach to controlled ovarian stimulation

for assisted conception,” Human Reproduction, vol. 24, no. 4,

pp. 867–875, 2009. - D. Navot, Z. Rosenwaks, and E. J. Margalioth, “Prognostic

assessment of female fecundity,” The Lancet, vol. 2, no. 8560,

pp. 645–647, 1987. - J. Kwee, R. Schats, J. McDonnell, J. Schoemaker, and C.

B. Lambalk, “The clomiphene citrate challenge test versus

the exogenous follicle-stimulating hormone ovarian reserve

test as a single test for identification of low respondersand hyperresponders to in vitro fertilization,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 85, no. 6, pp. 1714–1722, 2006.R - . C. Franco, R. A. Ferriani, M. D. Moura, R. M. Reis, R. A.

Ferreira, and M. M. de Sala, “Evaluation of ovarian reserve:

comparison between basal FSH level and clomiphene test,”

Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetr´ıcia, vol. 24, no. 5,

pp. 323–327, 2002. - A. Maheshwari, A. Gibreel, S. Bhattacharya, and N. P.

Johnson, “Dynamic tests of ovarian reserve: a systematic

review of diagnostic accuracy,” Reproductive BioMedicine

Online, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 717–734, 2009. - D. M. Ranieri, F. Quinn, A. Makhlouf et al., “Simultaneous

evaluation of basal follicle-stimulating hormone and 17βestradiol response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue stimulation: an improved predictor of ovarian reserve,”

Fertility and Sterility, vol. 70, no. 2, pp. 227–233, 1998. - A. Ravhon, S. Lavery, S. Michael et al., “Dynamic assays

of inhibin B and oestradiol following buserelin acetate

administration as predictors of ovarian response in IVF,”

Human Reproduction, vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 2297–2301, 2000. - D. J. Hendriks, F. J. M. Broekmans, L. F. J. M. M. Bancsi, F.

H. de Jong, C. W. N. Looman, and E. R. te Velde, “Repeated

clomiphene citrate challenge testing in the prediction of

outcome in IVF: a comparison with basal markers for ovarian

reserve,” Human Reproduction, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 163–169,

2005. - J. Kwee, M. W. Elting, R. Schats, P. D. Bezemer, C. B. Lambalk,

and J. Schoemaker, “Comparison of endocrine tests with

respect to their predictive value on the outcome of ovarian

hyperstimulation in IVF treatment: results of a prospective

randomized study,” Human Reproduction, vol. 18, no. 7, pp.

1422–1427, 2003. - G. J. Scheffer, F. J. M. Broekmans, C. W. N. Looman et

al., “The number of antral follicles in normal women with

proven fertility is the best reflection of reproductive age,”

Human Reproduction, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 700–706, 2003. - L. F. J. M. M. Bancsi, F. J. M. Broekmans, M. J. C.

Eijkemans, F. H. de Jong, J. D. Habbema, and E. R. Te Velde,

“Predictors of poor ovarian response in in vitro fertilization:

a prospective study comparing basal markers of ovarian

reserve,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 77, no. 2, pp. 328–336,

2002. - T. E. M. Verhagen, D. J. Hendriks, L. F. J. M. M. Bancsi, B. W.

J. Mol, and F. J. M. Broekmans, “The accuracy of multivariate

models predicting ovarian reserve and pregnancy after in

vitro fertilization: a meta-analysis,” Human Reproduction

Update, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 95–100, 2008. - M. L. Haadsma, A. Bukman, H. Groen et al., “The number

of small antral follicles (2–6 mm) determines the outcome of

endocrine ovarian reserve tests in a subfertile population,”

Human Reproduction, vol. 22, no. 7, pp. 1925–1931, 2007. - P. B. Maseelall, A. E. Hernandez-Rey, C. Oh, T. Maagdenberg,

D. H. McCulloh, and P. G. McGovern, “Antral follicle count

is a significant predictor of livebirth in in vitro fertilization

cycles,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 91, no. 4, supplement, pp.

1595–1597, 2009. - A. Gibreel, A. Maheshwari, S. Bhattacharya, and N. P.

Johnson, “Ultrasound tests of ovarian reserve; A systematic

review of accuracy in predicting fertility outcomes,” Human

Fertility, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 95–106, 2009. - B. Almog, F. Shehata, E. Shalom-Paz, S. L. Tan, and T.

Tulandi, “Age-related normogram for antral follicle count:

McGill reference guide,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 95, no. 2,

pp. 663–666, 2010. - C. H. Syrop, J. D. Dawson, K. J. Husman, A. E. T. Sparks,

and B. J. Van Voorhis, “Ovarian volume may predict assisted

reproductive outcomes better than follicle stimulating hormone concentration on day 3,” Human Reproduction, vol. 14,

no. 7, pp. 1752–1756, 1999. - S. Bowen, J. Norian, N. Santoro, and L. Pal, “Simple tools

for assessment of ovarian reserve (OR): individual ovarian

dimensions are reliable predictors of OR,” Fertility and

Sterility, vol. 88, no. 2, pp. 390–395, 2007. - D. J. Hendriks, J. Kwee, B. W. J. Mol, E. R. te Velde, and F. J.

M. Broekmans, “Ultrasonography as a tool for the prediction

of outcome in IVF patients: a comparative meta-analysis

of ovarian volume and antral follicle count,” Fertility and

Sterility, vol. 87, no. 4, pp. 764–775, 2007. - H. Tinkanen, M. Blauer, P. Laippala, P. Tuohimaa, and E. ¨

Kujansuu, “Prognostic factors in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 72, no. 5, pp. 932–936,1999. - K. Elter, Z. N. Kavak, H. Gokaslan, and T. Pekin, “Antral

follicle assessment after down-regulation may be a useful

tool for predicting pregnancy loss in in vitro fertilization

pregnancies,” Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 21, no. 1, pp.

33–37, 2005. - G. J. Scheffer, F. J. M. Broekmans, L. F. Bancsi, J. D. F.

Habbema, C. W. N. Looman, and E. R. Te Velde, “Quantitative transvaginal two- and three-dimensional sonography

of the ovaries: reproducibility of antral follicle counts,”

Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 20, no. 3, pp.

270–275, 2002. - S. Kupesic, A. Kurjak, D. Bjelos, and S. Vujisic, “Threedimensional ultrasonographic ovarian measurements and in

vitro fertilization outcome are related to age,” Fertility and

Sterility, vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 190–197, 2003. - K. Jayaprakasan, B. Campbell, J. Hopkisson, J. Clewes, I. Johnson, and N. Raine-Fenning, “Establishing the intercycle variability of three-dimensional ultrasonographic predictors of ovarian reserve,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 90, no. 6, pp.2126–2132, 2008.

- D. K. C. Chui, N. D. Pugh, S. M. Walker, L. Gregory, and R. W. Shaw, “Follicular vascularity-the predictive value of transvaginal power Doppler ultrasonography in an invitro fertilization programme: a preliminary study,” Human Reproduction, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 191–196, 1997.

- M. F. Costello, S. M. Shrestha, P. Sjoblom et al., “Power doppler ultrasound assessment of the relationship between age and ovarian perifollicular blood flow in women undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment,” Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, vol. 23, no. 9-10, pp. 359–365,

2006. - S. M. Shrestha, M. F. Costello, P. Sjoblom et al., “Power doppler ultrasound assessment of follicular vascularity in the early follicular phase and its relationship with outcome of in vitro fertilization,” Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 161–169, 2006.

- B. R. de Carvalho, A. C. Japur De Sa Rosa-e-Silva, J. C. Rosa-e-Silva, R. M. Dos Reis, R. A. Ferriani, and M. F. Silva De Sa, “Anti-mullerian hormone is the best predictor of poor response in ICSI cycles of patients with endometriosis,”

Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 38,no. 2, pp. 119–122, 2011.